UK lawmakers approve three-parent babies law

Soon, when your little ones ask where babies come from, you might have to think twice.

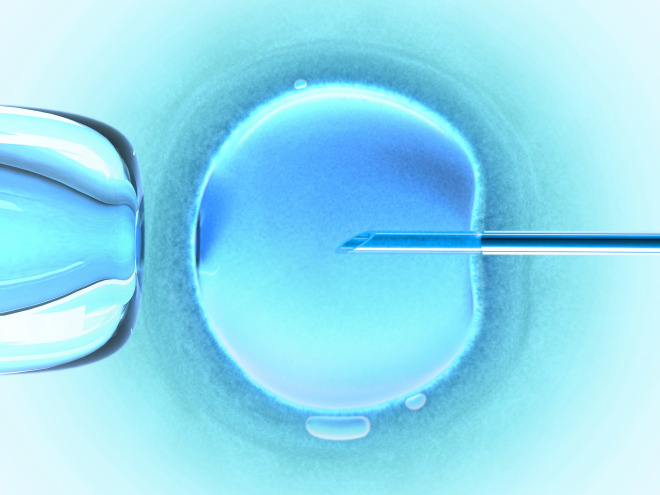

Last week, the UK’s lower house approved a bill that would allow IVF babies to be created using the DNA of three parents. The goal is to keep people with serious genetic diseases from passing them on to their kids.

This is how it could work: a tiny fraction of the mom’s DNA is swapped with that of an anonymous female donor, either before or after it’s mixed with the dad’s DNA. So even though the baby’s DNA would be almost entirely from two parents, there would be a little bit from a third person.

Supporters say this technique offers the only hope for some women who carried the disease to have “healthy, genetically-related children” who would not suffer from the “devastating and often fatal consequences” of serious genetic diseases (mitochondrial disease), according to an article in the UK Guardian. Critics say this crosses a major ethical boundary that could one day lead to “designer babies” – aka picking and choosing your child’s genes.

Mitochondrial diseases are caused by genetic faults in the DNA of tiny structures that provide power for the body’s cells. The DNA is held separately to the 20,000 genes that influence a person’s identity, such as their looks and personality. Because mothers alone pass mitochondria on to children, the diseases are only passed down the maternal line.

The bill just needs to be approved by the UK’s upper house before the country becomes the first in the world to allow this technology.

While this is no doubt a scientific step forward, it also steps into uncharted ethical areas. One of the procedures, called pronuclear transfer, involves “the deliberate creation and destruction of at least two human embryos, and probably in practice many more, in order to create a third embryo which it is hoped will be free from human mitochondrial disease,” said Jane Ellison, Conservative public health minister.

The Church of England’s national adviser on medical issues, the Rev. Dr. Brendan McCarthy, described the step as representing an ethical watershed and said more research and wider debate were needed.

“We accept in certain circumstances that embryo research is permissible as long as it is undertaken to alleviate human suffering and embryos are treated with respect. We have great sympathy for families affected by mitochondrial disease and are not opposed in principle to mitochondrial replacement,” he said. “Our view, however, remains that we believe that the law should not be changed until there has been further scientific study and informed debate into the ethics, safety and efficacy of mitochondrial replacement therapy.”

Another ethical issue that arises is this: Will we be allowed to pick and choose key characteristics of our children? And will people also seek to control skin color, eye color, hair color, or even something as uneasily defined as sexual orientation? Do we really want to live in a society of designer babies? Aside from the prospect being dystopian, it also risks reducing natural variation in the human race – which is critical to its adaptation and survival. If fashion dictates that certain characteristics should be eliminated, that could negatively affect future generations.

The other issue, of course, is that – technically – the baby would have three biological parents, with 99.8% of genetic material coming from the mother and father and 0.2% coming from the donor. Under British law, egg and sperm donation can no longer be anonymous – those born of such conceptions have the legal right to know where they came from, when they reach adulthood.

When it comes to mitochondrial transfer, ‘second mothers’ will remain anonymous, under the draft regulations. However, if a third party has contributed DNA to the creation of a child, they are effectively another parent. As such, children have a right to know their identity.

According to Ann Haralambie, author of Handling Child Custody, Abuse, and Adoption Cases, published by Thomson Reuters, there are many cases of assisted reproductive technology where an embryo created by one woman’s egg is gestated by and born to a surrogate (known as “gestational surrogacy,” as opposed to “traditional surrogacy,” where the surrogate’s own egg is fertilized by the man’s sperm).

“Some lesbian couples, for example, have one woman donate an egg and the other woman give birth to the baby through in vitro fertilization, allowing both women to assert their maternity through the traditional methods of legal proof,” said Haralambie. “The Nevada Supreme Court has held that the Nevada Parentage Act, modeled after the Uniform Parentage Act, did not preclude a child from having two legal mothers where one mother donated the egg and the other gestated and gave birth to the child, noting that, given the medical advances and changing family dynamics of the age, determining a child’s parents today can be more complicated than it was in the past.” (WestlawNext users see St. Mary v. Damon, 309 P.3d 1027, 1032, 129 Nev. Adv. Op. No. 68 (Nev. 2013).

A number of cases have construed the Uniform Parentage Act as recognizing two same-sex parents based on various presumptions of parentage. “For all surrogacy cases, the trend is definitely to recognize the ‘intended parents’ as the ones given legal recognition,” Haralambie continued. “However, there have been a few cases involving known donors in gestational surrogacy achieved without the assistance of doctors (the so-called ‘turkey baster’ inseminations) where both mothers and the father were recognized as having parental rights.”

In 2013, the California legislature enacted SB 274, allowing for legal recognition of more than two parents. It is possible for a donor egg and donor sperm to result in an embryo implanted in a gestational surrogate and then given to an “intended couple” as their child, resulting in five people with some claim to parentage.

“Embryo ethics aside, from a legal standpoint I don’t see this new law creating three parents in any meaningful sense of the word ‘parent,’” added Haralambie. “Conceptually, this can be thought of as a mitochondrial transplant, legally similar to any organ transplant.”

Around 40 scientists from 14 countries have urged the British legislature to approve laws allowing mitochondrial DNA transfer.