We Are All Criminals exhibit comes to Thomson Reuters Eagan, MN campus

We’ve all committed a crime at some point in our lives, either knowingly or not and either petty or major. There was that time in high school when you and your friends thought it would be funny to steal that street sign. Or that time in college when you experimented with illegal drugs. Or that time after the office happy hour when you may have had one too many drinks, but drove home anyway because you thought you were fine to drive. In fact, 75 percent of us in the United States have done these things or worse, yet we’ve had the luxury to forget about them.

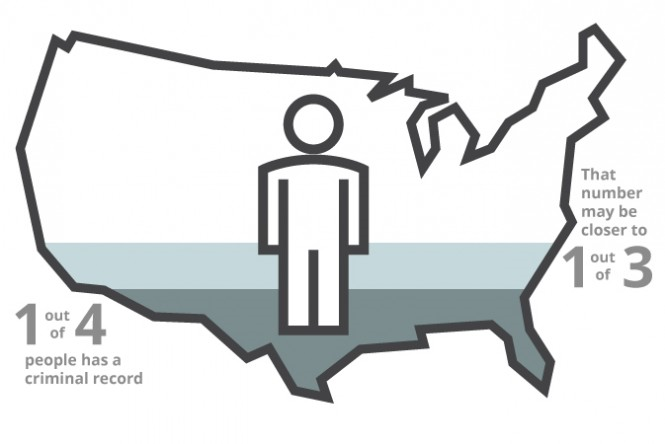

In the U.S. today, one in four people has a criminal record for something other than a minor traffic violation. This record is used by the vast majority of employers, legislators, landlords and licensing boards to craft policy and determine the character of that individual. In our electronic and data age, it typically does not disappear, regardless of how long it’s been or how far one’s come. It’s a record that prevents not only professional licensure and a gainful career path, but can also get in the way of obtaining entry-level positions, foster care licenses, entry into college, and safe housing. To bring this point home, someone who was arrested eight years ago as a teenager for stealing one bottle of Michelob Golden Light from a liquor store cannot obtain employment at a pari-mutuel betting establishment (i.e., a horse track) shoveling animal waste.

This is where Emily Baxter, a Bush Fellow and the director of public policy and advocacy at the Council on Crime and Justice, comes in. Her clients are the men, women, and youth who can’t find housing or employment, can’t get into school or secure a loan, can’t obtain professional licensure or cast a ballot, because of a criminal record. For the last several years, she’s been advocating on behalf of her clients to legislators and landlords, employers and licensing boards – as well as the general public, seeking second chances. More times than not, the answer was, “once a criminal, always a criminal.”

According to Baxter, her approach changed a couple of years ago. “I received a Bush Leadership Fellowship, and through it the incredible opportunity to reconsider my approach to work,” she said. “It was then that I began exploring the idea that this fictionalized dichotomy of ‘us’ versus ‘them’ – or ‘clean’ versus ‘criminal’ was really at the heart of the problem.”

Baxter decided to send out fliers, asking people to tell her about crimes they got away with. Amazingly, the phone started to ring. And it hasn’t stopped.

We Are All Criminals is the result of those stories. This project looks at the other 75 percent: those of us who have been able to live without an official reminder of a past mistake. Baxter drove around the state of Minnesota to meet with and photograph the people who responded to her flier. The photographs, while protecting participants’ identities, convey personality: each is taken in the participant’s home, office, crime scene, or neighborhood. The participants are doctors and lawyers, social workers and students, retailers and retirees who consider how very different their lives could have been had they been caught.

The stories are of youth, boredom, intoxication, and porta-potties. They are humorous, humiliating, and humbling in turn. They are privately held memories without public stigma; they are criminal histories without criminal records.

Baxter has collected well over 200 stories to-date; a portion of those include photographs and are featured on the website. She has another twenty that will be going up over the next couple of months, and she continues to interview people each week. Not everything is published; some participants have shared their stories with her but asked that they go no further. “I respect that, and am grateful for even that limited participation,” said Baxter. “It means they’re taking the project to heart.”

When Baxter visited the Thomson Reuters campus in Eagan, MN last week to discuss the project, she said that We Are All Criminals aims to challenge society’s perception of what it means to be a criminal and how much weight a record should be given, when truly – we are all criminals. But it is also a commentary on the disparate impact of our nation’s policies, policing, and prosecution: many of the participants benefited from belonging to a class and race that is not overrepresented in the criminal justice system. Permanent and public criminal records perpetuate inequities, precluding millions of people from countless opportunities to move on and move up. We Are All Criminals questions the wisdom and fairness in those policies.

“We Are All Criminals seeks to remind viewers and readers that while we have all done something we are not proud of, we are also all human and may be in need of a second chance,” said Baxter. She nails home this point by demonstrating parallel stories of similar crimes on the We Are All Criminals website. One example is the parallel story of the sale and possession of controlled substance, highlighted below.

Private memory: “When I got to college, I was one of the few freshmen who both smoked and knew someone who sold weed. I started buying for friends, and then friends of friends. A few months in, I was buying ounces at a time, and then expanded to acid. I’m not really in the demographic associated with dealers, and my customers were people I wouldn’t have interacted with normally: footballers and frat bros. I guess that’s a lot of why I did it—that and breaking whatever stereotypes. By junior year, it became less about having weed conveniently for my friends and myself, and more about keeping up with what people expected of me. After the last batch, I began redirecting my customers to another person. I miss them more than I thought I would.”

Public record: “She started selling her ADHD medication to the popular girls once she realized a few pills could transform her from a complete geek to someone that would occasionally get a ‘hey’ in the hallways. She sold a few pills here and there in college, too. At least, she did until she was caught. She was charged with a felony, suspended from school, and lost her scholarship. Now, sometime later and after a year of nursing school, she found out she’s ineligible for licensure till she turns 32.”

So, what’s your story? Visit the We Are All Criminals website to learn more and submit your story.

*Photo taken from the We Are All Criminals website.