Mitchell and Mitchell On Health Care and the Trump Agenda, Part 6: Proposed AHCA Bill Had Serious Flaws

This is the sixth post in an ongoing series regarding changes in health care that may take place—and actual changes that do take place—with the Trump administration. The likely implementation issues to be encountered for both potential and actual changes are described, based on detailed methods of analysis. The emphasis is on what these shifts mean for legal practices and how attorneys may prepare in the most effective ways.

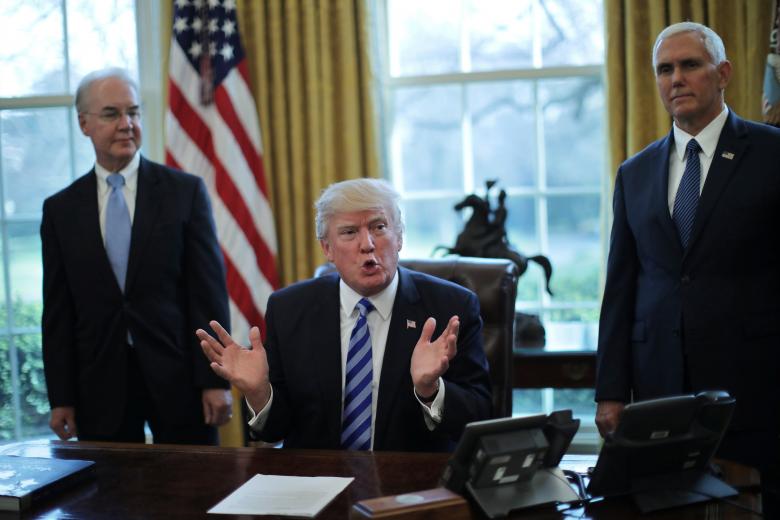

The proposed American Health Care Act (AHCA) that was withdrawn on March 24 had a number of serious flaws that need to be recognized to aid in future design efforts. An effective approach to understanding such flaws may be based on the ways in which groups of individuals and types of organizations are likely to react to any pending law. The approach to analyzing the plan here is based on past studies of reactions that are likely to develop when program changes take place, as discussed in part one of this series.

The AHCA bill sought to include the conversion of Medicaid to block grants; replacement of subsidies under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) with tax credits combined with more flexibility in the essential health benefits covered by insurance policies; and removal of the mandate for employers to provide health insurance to employees. All three of these design features would have affected access to health coverage and the costs incurred by individuals, government agencies, and employers.

The intent of Medicaid block grants was to allow states to revise program requirements and to cap federal expenses. Some lower-income individuals would then likely experience less coverage—and possibly more restrictions in obtaining care. Those providers accepting Medicaid would experience reduced income.

A shift from subsidies to tax credits was intended to reduce government expenses for health care and encourage more individual decision making about coverage. With more flexibility, some individuals might decide to take the risk of less health insurance in order to pay for other personal needs. The inevitable conclusion would be that some individuals would be unable to pay for unexpected medical costs. This would likely result in hospitals having to provide more unpaid care.

Employers have often been motivated to provide group health insurance to employees because such contributions are considered tax-deductible business expenses. However, tax credits were intended to equalize the tax situations for individuals. If the employer mandate were to be removed, it might be attractive for companies to eliminate group coverage, increase wages and other benefits, and encourage employees to buy individual insurance with tax credits. (The tax credits would likely not be available where employer-based coverage was offered.) The risk in this scenario would be a decrease in employer group insurance. In turn, individuals would have then purchased less-expensive individual policies, leaving more unpaid expenses to be written-off by providers.

From all three viewpoints, some affected individuals would likely have experienced less access in coverage with more out-of-pocket costs. Many providers also would likely see reduced income. As noted in part five of this series, both individuals and providers would be motivated to push back against the AHCA as it was designed.

The advocates for the AHCA seemed to hope that rapid economic growth across the U.S. would help counteract the negative reactions to the new plan. If the economy were to expand rapidly, so the thinking went, more funding would be available to individuals and providers to allow them to adjust to the situation. As discussed in part one, timing and the external setting are essential features to consider in any program implementation. In an economically-expanding setting, some positive reactions might have helped balance the likely negative reactions noted above.

This post was written by Ferd H. Mitchell and Cheryl C. Mitchell, Thomson Reuters authors and attorney partners at Mitchell Law Office in Spokane, Wash. They are active in elder law and health law practice areas and have been working together on programs and activities on behalf of the elderly and in health care for more than 25 years. During their studies, they have visited and evaluated the health care systems of Japan and several countries in Europe to learn how the needs of the elderly are assessed and met in other countries, and they have been better able to understand the U.S. health care system and related care issues from these visits. More about the lessons learned from the ACA and issues involved in health program changes may be found in the 2017 edition of the authors’ book, Legal Practice Implications of Changes in the Affordable Care Act, Medicare and Medicaid, published by Thomson Reuters. More about these methods of analysis may be found in Mitchell & Mitchell, Adaptive Administration, published by Taylor and Francis. Click here to read part one of this series, here for part two, here for part three, here for part four, and here for part five.

The views and opinions expressed in this post are those of its authors alone.